A California employer, Randazzo Enterprizes, Inc., has sued Applied Underwriters’ for fraud in connection with Applied’s EquityComp program. It is a unit of Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK).

The complaint alleges inaccurate representations were made by Applied Underwriters to encourage the transaction. At issue are claims of fraud for allegedly misrepresenting the facts about the program and for allegedly increasing premiums more than it was allowed to based on an undisclosed formula. The formula is not filed with the California Department of Insurance. The employer says the unpredictable nature of the workers’ comp premiums billed under Applied Underwriters’ EquityComp program made it impossible to manage its business and bid on projects.

After nearly two years in the program, Randazzo had one closed claim totaling approximately $30,000. There was a second claim for a broken arm that happened on the last day of the second year and which Applied was not yet aware of for premium calculation purposes. Applied more than tripled the monthly charges to some $94,000. At this point Randazzo canceled. Applied filed for cancelation fees, which provoked the fraud suit.

The employer is seeking a rescission of the policy – a move that would entitle it to “a return of all premiums paid less any amounts paid for claims.” Applied Underwriters Captive Risk Assurance Company (AUCRA) fought back. So far, the employer has principally prevailed.

Randazzo filed the complaint in the Northern District of the United States District Court. Applied fought back filing motions for dismissal and to have the case go to Arbitration. The federal court ruled for Randazzo in two key areas: Applied was rebuffed in its effort to have the case dismissed outright; The court, while granting Applied’s Motion for arbitration, ruled for Randazzo in holding that a portion of the arbitration clause in Applied’s Reinsurance Participation Agreement (RPA) is both procedurally and substantively unconscionable.

The arbitration provisions used in the AUCRA contract allowed AUCRA to seek injunctive relief in the event of a breach or threatened breach of the agreement while the employer could only access the courts after prevailing in arbitration.

In requiring the case to go to Arbitration, it gave a major point to Randazzo: Randazzo succeeded in having the arbitration held in California. Applied’s agreement required that arbitration was to take place in Tortola, the British Virgin Islands.

The Arbitration decision clause is relevant because it is Applied’s standard deal and contained in principally all of the RPA agreements Applied has in California. It is not, however, a precedent. These arbitration clauses are being challenged around the country.

The case is separate and distinct from the dispute currently pending before a California Department of Insurance administrative law judge, (see the Shasta Linen case on page 1). It alleges a similar pattern of abuse, nondisclosure, and use of non-filed rate plans.

The Fraud

The Fraud

At the root of Randazzo’s complaint is how charges and deposits in the event of claims were to be calculated and collected. That leads to what it says is the unpredictability of what it was being charged in any given month for its workers’ comp policy.

Randazzo’s position is that that the RPA ‘cannot be read sufficiently to follow the pricing formulas.’ The charge is consistent with statements and testimony in the Shasta Linen case.

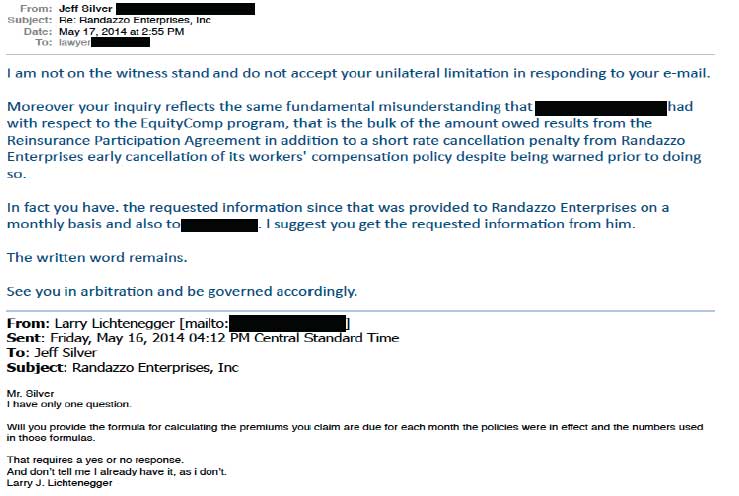

The company maintains that it made numerous requests, but Applied has refused to provide a formula that could be used to recreate the charges it received (see the image of Randazzo’s exhibit below). Additionally, it maintains that Applied used a different formula than it was told would be used at the outset of the program to calculate charges.

Randazzo claims that it was understood at the beginning that, for the first year of the three-year program, its premiums would be tied to the number of employees and wages paid multiplied by the rate for each class and by a “pay-in factor” of 70%. Additionally, for the first year its monthly premiums were supposed to be fixed using these rates and this pay-in factor and Randazzo’s estimated payroll, but it says that changed early in the game.

Four month’s into the program a Randazzo employee suffered a broken arm and the claim ultimately cost just over $30,000. In the first month after the accident it says Applied began using a higher pay-in factor than agreed that resulted in an average increase in its monthly bill of over $8,000 or roughly a 43% increase.

Randazzo cried foul noting that the pay-in factor was supposed to be locked in for the first year of the agreement and that Applied was using a higher factor just five months into the program. The parties resolved this disagreement before the first-anniversary date and Randazzo continued for another year, although there continued to be a dispute over how much of a credit Randazzo was due.

During its second year in the program it says it continued pressing for a formula that would allow it to estimate its premiums accurately but never received an adequate response. The company also incurred a second claim – another broken arm – that it says eventually amounted to $40,997.16.

During its time 26 months before it canceled the program Randazzo paid $551,528.51 into what Applied called a protected cell account established by the policy. The company by this time had two [closed] claims totaling just over $80,000.

At the inception of Randazzo’s third year in the program, according to the complaint, Applied raised the premium to more than three times the previous monthly premium to approximately $94,000.00. Attorney Larry Lichtenegger says the increase was without “any justification or representation as to its validity.” Randazzo refused to pay the increase and canceled the policy and the program.

“Based on the information provided and in spite of Applied Underwriters contention to the contrary, Randazzo has been unable to duplicate the premium calculations made by Applied Underwriters,” says the complaint. “It appears that Applied Underwriters, in violation of the initial representations, calculates premium obligations based on estimates of future payroll and future claims, but without any justification for such estimates.”

Unfiled Policy or Rates

Randazzo also challenges Applied’s assertion that the program was a reinsurance agreement and maintains that it is more akin to a retro policy albeit with its own unique wrinkles. It maintains that this alleged misrepresentation alone is justification for a recession of the policy and the return of premiums totaling nearly $500,000.

“Applied Underwriters, by and through its agents and representatives, intentionally and /or fraudulently misrepresented to Randazzo material facts,” says Lichtenegger in the original complaint. “It failed to advise Randazzo that Applied was not registered [at the time] with the California Secretary of State,” and that “the policy of insurance it was selling was not approved by the California Department of Insurance as required by Cal. Ins. Code § 11658; the true nature of the Agreement, the excessive fees, surcharges, penalties, and premiums contained in the Agreement, and that, after first representing that this was a standard ‘retro’ policy with a built-in profit sharing provision. It failed to advise Randazzo that it intended to calculate premiums based on its own estimates of future payroll and claims …”

Following Randazzo’s cancelation of the policy because of the tripling of its monthly premiums, Applied filed an arbitration demand for additional payments of $430,451.01, which include an early cancelation penalty.

It was that demand that prompted Randazzo’s complaint, which in addition to rescission of the policy and a return of all premiums is seeking punitive damages as well. “There is clear and convincing evidence that Applied Underwriters’ actions were intentional, fraudulent, malicious, or reckless,” Lichtenegger maintains.

Randazzo will also be alleging that Applied misrepresented the facts about the program to get it to join and breached the RPA by increasing its premiums.

Workers’ Comp Executive attempted to include Applied’s side of the story. It tried to obtain comments from both Applied and Berkshire Hathaway, but both companies declined to comment. WCE did receive an email from Attorney Spencer Y. Kook, of Hinshaw & Culbertson, LLP, the law firm representing Applied. It read, “The client has no comment and will not discuss ongoing litigation. Thank you.”

Applied Underwriters was once but is no longer an affiliate of Berkshire Hathaway. Applied’s management bought it. Berkshire Hathaway bears no responsibility for any of the events which have transpired involving Applied Underwriters’ or its subsidiaries including California Insurance Company.